Chile, Country of Volcanoes: A Passion for these Giants’ photography

By: Chile Travel - 13 August, 2020

Did you know that Chile is the country with the Americas’ largest number of active volcanoes? This is the reason why geological tourism and fascination with Chile’s volcanoes is an increasingly popular and widespread phenomenon in our country.

Who knows plenty about the subject is Argentinian photographer Diego Spatafore, who has almost exclusively dedicated his life to volcano photography. These giants’ exploration is his passion and the reason behind flying in helicopters to watch up close these impressive ranges’ amazing craters, a routine that started in 2007 while he was in southern Chile.

He experienced the eruption of the Llaima volcano in 2008, something that deeply marked his life: “That’s when I started this misunderstood passion for volcanoes. To me, they are life’s beginning and one of the greatest shows that nature provides us.”

Among the thousands of Chilean volcanoes, there are some that are an essential part of our history, whether due to their eruptions, geological heritage, or connotation for our indigenous culture. These volcanoes, in addition to being the most visited in Chile, are perfect for photography fans; as Diego tells us: “Without a doubt, the Chile’s most symbolic volcano is the Villarrica, one of the seven volcanoes in the world that has active lava flow that can be seen from its crater. I also like the Sollipulli, the Puntiagudo, and the Corcovado, they are gorgeous.”, says Diego.

His great passion and knowledge are reflected in his images depicted in several books, including his latest: Terra Volcano. Through this book, you can tour southern Chile following his astounding pictures painting a unique story of our volcanic geography, including the Llaima, Villarrica, Caulle, Puntiagudo, Osorno, and Calbuco volcanoes.

All these efforts are aimed at promoting geological tourism, which, according to Diego, will transform our country into a world power: “After Indonesia, Chile is one of the countries with the world’s most active volcanoes and South America’s two most active volcanoes: the Llaima and the Villarrica. The creation of the Araucanía’s Kutralkura Geopark and its recognition by UNESCO steers Chile to becoming a world leader in geological tourism.”

Finally, this “madness” triggered by volcanoes has led Diego to witness several eruptions. “I have been fortunate to see and capture the eruptions of the Llaima in 2008 and 2009, Caulle 2011, Copahue 2014, Villarrica and Calbuco 2015, and the eruption of the Chillán volcano last year.”

He confesses that it is not easy, that luck, passion, and knowledge play in his favor, since you have to “dare to run in the opposite direction to record the most beautiful shots of this manifestation of nature”, he says enthusiastically.

If you are a volcano fanatic like Diego and want to learn more, here we will go over a brief guide of Chile’s most symbolic and popular volcanoes, so those that want to join this world can become acquainted with the volcanic and geological treasures we have, from north to south.

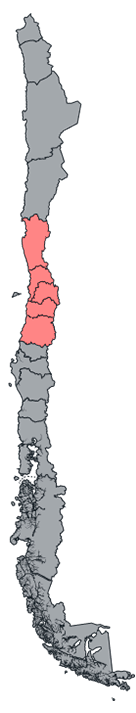

In the Far North: Guallatiri

A millennial volcano that the locals also know as Huallatiri, Huallatire, Guallatire or Punata, near the Bolivian border, at the southwestern end of the volcanic chain Nevados de Quimsachata.

At 6,063 meters above sea level, it is not far from the village of the same name, Guallatire, a pre-Hispanic town with narrow streets where the XVII century church facing the volcano stands out, surrounded by a wall and featuring a beautiful bell tower with corner pinnacles, all painted with white lime.

In addition to this magnificent volcano, within the territory of Guallatire and near the Pisarata settlement we also find the relics of a colonial trapiche (mill) that operated for a gold washing area.

Parinacota: One of the Payachatas’ Gods

The Parinacota volcano, along with its sibling, Pomerape, make up the Nevados de Payachatas range. Both “Gods”, according to the Altiplano population’s mythology, the Parinacota is the oldest sibling with 6,342 meters of altitude, and is one of the Atacama Desert’s typical images.

From the town of Parinacota, the best way to enjoy nature is hiking. On the way, Lake Chungará (at 4,500 meters, one of the highest in the world) amazes us with its rare and peculiar wildlife of chinchillas, vizcachas, vicuñas, and pink flamingos that color the lake with their beautiful plumage.

To reach the Parinacota’s summit, you must climb a steep glacier that begins at 5,200 meters, making the destination suitable only for experienced and properly equipped hikers.

Those who reach the summit are rewarded with the sight of a 300-meter wide crater, whose last eruption has been estimated to around 160 centuries ago, covered with lava and ashes a vast area of the surroundings.

Those of us that choose not to climb can enjoy the volcano’s view from Lake Chungará in the Lauca National Park, the most representative of the Altiplano.

The Highest Active Volcano on Earth: Ojos del Salado

The highest volcano on Earth, measured from sea level to the summit or crater is the Nevado Ojos del Salado.

It is considered active, despite not recording eruptions in historical times. Its activity is evidenced, however, by the frequent vents that surface throughout the summit.

At 6,893 meters above sea level, it is the largest neighbor of a mountain and volcanic chain exceeding 6,000 meters in one of the most unexplored, wild, and desolate regions of the Chilean Andes.

The Nevado Ojos del Salado is one of the best mountain climbing spots in Chile. Climbing the volcano is the goal of climbers from all over the world that visit us every year during the climbing season (November – March).

There are several excursions available, weather permitting, which can take up to 8 days. Two shelters, the first at 5,100 meters and the second at 5,750 meters, ease a bit the harsh climb for the more adventurous.

The less adventurous will marvel at the view from its slopes, accessible through the international route CH-31.

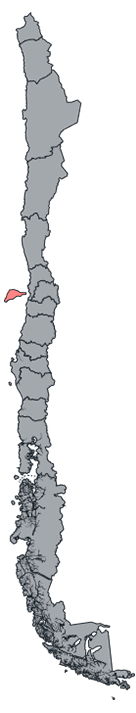

Lonquimay: The Little Big Volcano

By comparison, perhaps the Lonquimay (“Dense Forest” in the Mapuche language) is the smallest of the volcanoes we have mentioned, and yet its last eruption lasted over a year, between 1988 and 1989!

The Lonquimay, located in the beautiful Malalcahuello National Reserve, has an older sibling: the Tolhuaca, with its steep slopes opposing the Lonquimay.

Its surrounding’s landscape is amazing: after a lush and typical Chilean Pine forest, the vegetation abruptly gives way to a lunar landscape of ash and rock, reminiscent of the most recent eruptions.

A large lookout offers a breathtaking view of the summit and the side crater that emerged after the December 25th, 1988 eruption, date responsible for the “newly-born’s” name, Navidad crater.

From the lookout and its surroundings, other volcanoes reshape the horizon, reminding us of the region’s location, powerful and inspirational.

The ashes and volcanic stones of different sizes that covered the slopes did not end life: among the stones emerged victorious numerous small flowers, restless and invulnerable as nature itself.

Llaima: Ashes, Lake, and Chilean Pines

The Conguillío National Park is one of the most spectacular national parks due to its unique beauty, featuring among its attractions the magnificent Llaima volcano.

Its last eruption was in 2009, but during the XX century experienced at least 23 events. It is visible from the neighboring city of Temuco, approximately 70 kilometers away, and its spectacular surroundings make it one of the preferred tourist destinations for Chileans and foreigners alike.

With an impressive Chilean Pine forest, lake, park, volcanic slag, forests, and mystical trail landscapes, the area is home to geological treasures that date back centuries.

Like all volcanoes, the Llaima is a sacred place for the Mapuche people with strong supernatural dimensions. The Mapuches say that the Llaima’s bowels and calderas are ruled by an elemental nature being, a ngen, the volcano’s ruler.

Ngen-winkul is the spirit of volcanoes and hills. Along with the presence of the ngen, the Llaima hosts a court of pillanes, minor but extremely powerful beings.

For the Mapuches, the Llaima is, then, a volcano of bad omens, in contrast with the Villarrica volcano, considered a “good volcano” responsible for constructive dreams.

Diego Spatafore recorded the Llaima’s eruption in 2008 and was the beginning of a passion that, 12 years later, still does not leave him. The Llaima is part of his photo collections and countless excursions he has personally organized.

The Good Volcano: The Villarrica

One of the most active volcanoes in Latin America is the Villarrica or Ruca Pillán (home of the pillán in the Mapuche language).

An almost perfect snow cone, like the cones Chilean children draw at school, the Villarrica inspires good dreams and “good weather”; and it is symbolically linked to miscellaneous positive elements; violet and green shades, the moon, and the stars.

It is part of the Villarrica National Park and it also includes a ski center with slopes for all levels and an excellent tourist infrastructure.

But in addition to snow sports, snow hiking, and mountain climbing are also enjoyed on its slopes. Those who have climbed its summit have witnessed its surroundings covered with local plant species such as oak, raulí, coirón, and lenga beech, as well as its hare, puma, and fox wildlife.

Diego Spatafore concedes that Villarrica is his favorite volcano, since he has not only captured it countless times, but also witnessed its eruptions, and, as he points out, is one of the most active volcanoes in South America.

In Lake Llanquihue’s Mirror: The Osorno Volcano

The Osorno Volcano is another one of those volcanoes that seem to be sketched into the landscape with its perfectly snowed top, dominating Lake Llanquihue. Very similar to Japan’s Mount Fuji, its summit is relatively easy to access and can be reached with relatively little help.

From the heights, you can also see one of its extinct craters, in surprisingly reddish tones, and learn from its important geological history.

The eruption of its neighbor, the Calbuco volcano, in 2005, covered its slopes and surroundings with ash. The ashes’ steely gray and volcanic rock formations with which the Calbuco covered the Osorno can still be seen towards the summit.

Further down, the vegetation has become even stronger, stimulated by the ashes’ fertilizing effect, reviving the forest’s green and the shrub layer. On the way back, it is an excellent idea to visit the Petrohué Falls.